Liikennematto devlog series

- Prototyping traffic simulation with Elm

- Build your own roundabout!

- Lots to do

- Hello real-time traffic simulation (this post)

- Renovation and release

Liikennematto started it's life as a rough traffic simulation that works like a board game. Cars took turns to roam around a tile based "board", and could move one tile at a time. This allowed rapid prototyping of basic traffic rules, yet the movement was blocky. In October of 2020 I set out to change the feel of Liikennematto. The goal was to have the cars move gradually at 60 frames per second. The speed of a car should control how much movement happens on each frame.

I vastly underestimated how much work that would take. So here I am, eight months later, ready to write about the journey.

Step 1: Building the road network graph

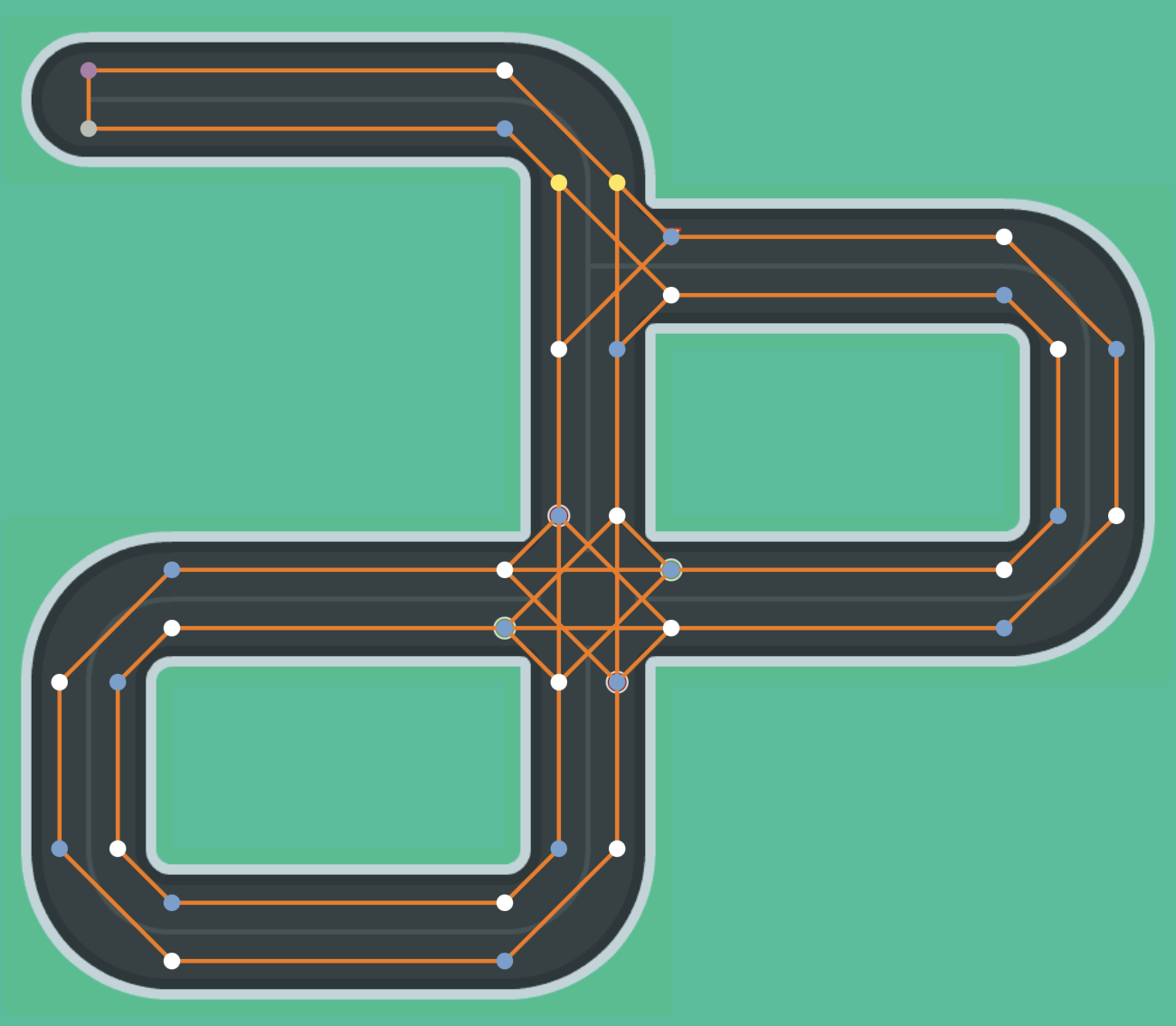

The tilemap was originally translated into a grid of "cells". Each cell contains a piece of two-lane road or an intersection. The precision of such a data model was not practical for sub-tile movement and the model didn't suggest how the cars should move. Graph, on the other hand, is a natural model for describing intersections and lanes between. Graphs are used in route planners and navigation systems, and common pathfinding algorithms traverse graphs as well. Liikennematto uses the solid Elm community graph library.

I worked out the relative position of lane start and end points from the tiles. Each intersection, curve and dead end has two or more nodes that model the connections between lanes. For instance, a T-intersection has 3*2 = 6. Each node has at least one edge to another node - the lane. This allows the graph to be directed, as the lane only goes one way. I also considered modeling the nodes as so-called "segments" with one bi-directional edge to another segment. This is the approach used in Cities Skylines, for example. A segment-based graph may have fewer nodes and is flexible with how lanes are configured, but requires translation of lane start and end points. I preferred the directed graph approach for Liikennematto because I find it easy to reason about.

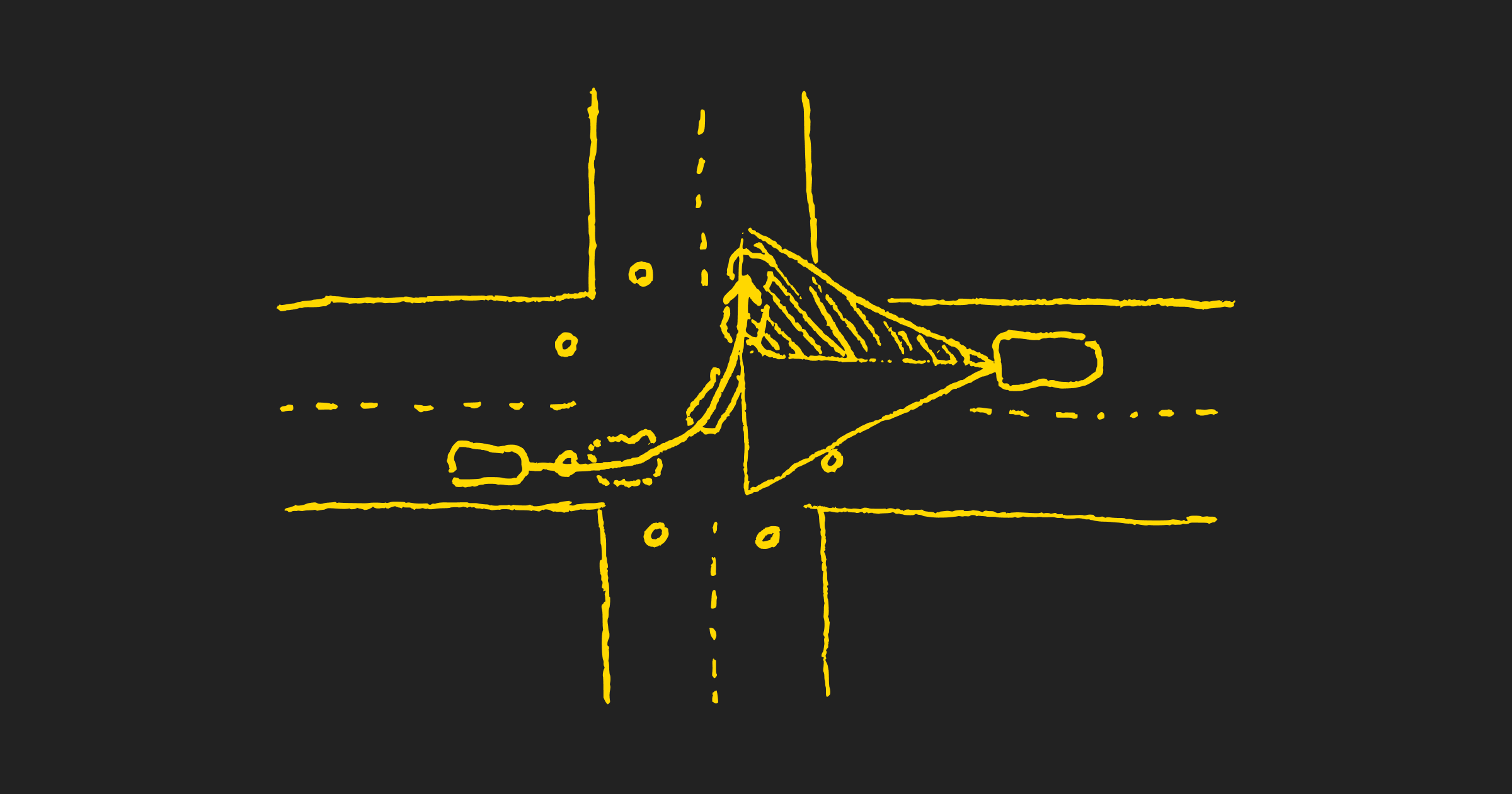

I tagged the nodes by their function. A node may be a lane start point, end point, a stopgap in a complicated multi-tile intersection, or a lot entrance. Deadends have their own node types, so that the cars can make a u-turn. I used the tags to create edges from lane start to lane end, from dead end entry to dead end exit, and so on. The mapping process works out the edges inside an intersection, too. Nodes carry other information, like their position in the tilemap, and their direction of travel. Here's the result visualized by one of the new debug tools in Liikennematto:

Step 2: Guiding cars through the road network

Cars normally enter the road network from the parking area of their lots. From there on they try to make their way to the next node. Once they get there they choose one of the connected nodes as their next target. Then the cycle repeats. This is equivalent to the old wandering logic where cars moved from tile to tile at random.

In the video above the cars simply turn instantly to face their target. They always move at maximum speed as well. This is not how cars work in real life!

I solved the unrealistic rotation by introducing "local paths" for cars. When a car reaches a node, the simulation plots a cubic bézier curve to the next node. Some node combinations have a special curve, like the dead end entry and exit, which require a tight u-turn. The curve is transformed into a polyline (list of points that form line segments) so that the car has more precise targets to aim for. This is a bit of a hack, as the smoothness of the rotation is based on how many line segments are used. There exists a whole family of steering algorithms that allow finer rotation, which I have been experimenting with lately.

Cars now have a velocity that is affected by changes in acceleration. If there's nothing special going on, the car is accelerated by a constant and somewhat realistic value until the car reaches target velocity. Cars may decelerate e.g. to avoid a collision, or to stop at traffic lights.

Games and simulations often use plain floats or vertices to work with acceleration, velocity, orientation, and such. I'm using the elm-units library instead. elm-units provide type-safe units of measure. The units are floats or integers that are tagged in a way that the Elm compiler can keep track of their usage. Arithmetic operations on units may result in special Rate (of change) and Product types, which have their own operations. Using an illogical combination of units, rates or products is a compile error. The types are discarded in the compilation phase, so there's no performance penalty. Here's an example: the velocity of a car is of the Speed type, or meters per second. I can add some Acceleration (meters per second squared) to the velocity once the acceleration is multiplied by a Duration (seconds).

car.velocity

|> Quantity.plus (car.acceleration |> Quantity.for delta)

|> Quantity.clamp Quantity.zero maxVelocity

Had I accidentally used AngularAcceleration (radians per second) instead of acceleration, the mistake would have been easy to spot.

elm-geometry builds on elm-units. It provides common 2D and 3D data types like points, polylines, triangles and direction vectors. The geometry is bound to a specific unit of measure, and to a coordinate system. The length of a line segment may be measured in meters or pixels, for example. Like with elm-units, it's impossible to mix up different units of measure. The Liikennematto simulation is based on meters and "Y-up" coordinates. The meter values are explicitly translated into pixels in the rendering phase. The cubic bézier curves mentioned before in this post are also something that elm-geometry provides.

Ian, the author of both libraries, is active in the Elm Slack. He helped me immensely while I learned the libraries and stumbled my way through the simulation rewrite. Thank you, Ian!

Step 3: Avoiding collisions

Cars roaming around the road network did not care about each other. In the old system, cars did not enter a cell if it was occupied by another car unless the car was on a different lane. The system was pretty extreme but worked. Given the vastly more complicated paths cars could take at this point, I had to think again.

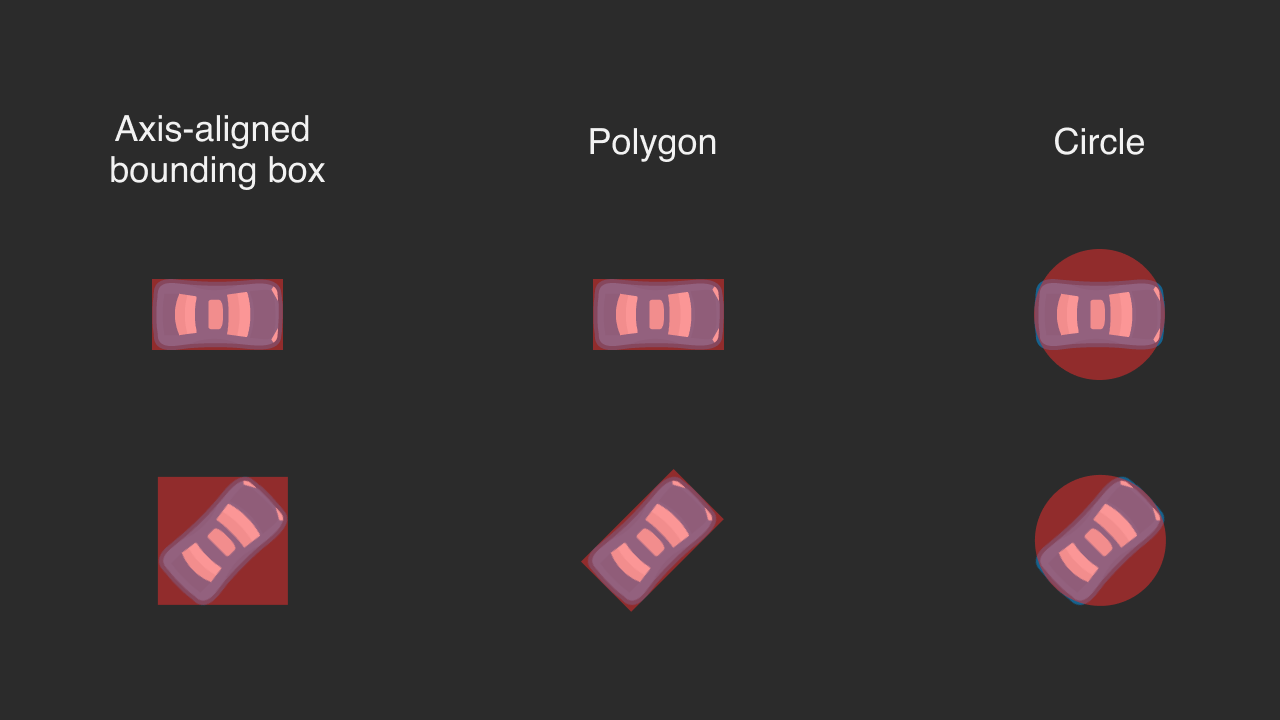

Collisions can be prevented quite easily. Cars can simply compare their bounding box to the other cars' one, and halt if there's a collision between them. This approach has two key problems: halting implies infinite deceleration, and both cars will probably make the same decision — they will never move again. This is why I implemented collision avoidance instead. Cars now look a bit ahead in time and predict how the other car is going to move. The distance and velocity of cars are taken into account. If it looks like there will be a collision, the car will decelerate to let the other car pass (or vice versa). Both cars may still choose to stop, so I had to think of a way to just have one of the cars react. The key is to only check cars that are on the right side of a car's field of view (point in triangle check). If everyone checks their right, two cars should not make the same decision. The field of view is based on the velocity of the car, by the way!

The collision avoidance gets more precise once another car is roughly in front of a car. A simple axis-aligned bounding box is not realistic for e.g. a car that has an orientation of 45 degrees. Some compare circles that cover the object completely, but they are roughly as imprecise. I use a polygon that is very close to the shape of the car, but has as few sides as possible. In the precise collision check a car casts a ray in the direction of their movement. If the ray intersects any of the sides of the polygon, a collision is imminent. The car reacts based on the distance to the collision.

Getting the collision avoidance system right took quite some time. I tried a bunch of different algorithms and collision object shapes. I had a (novel?) idea of comparing cars' local paths to see if they meet at some point. This would give an extremely reliable result, but the approach had too many edge cases and was computationally expensive.

Given that the collision check is meant to be performed once per frame for each car (every 17ms or so), the performance matters. If all cars check every other car, the check will run in quadratic time. You can't get rid of the linear time of updating every car per frame, but the cross-check can made logarithmic with tree-based 2D search of nearby cars. I use a quadtree for this. The quadtree library uses elm-geometry data types, which is handy. For the first time I used elm-benchmark to compare implementations. The speed difference was obvious with a large amount of cars.

I should note that though I have a functional collision avoidance system, cars may still end up in a gridlock. Sometimes cars simply don't have enough time to react. Sometimes the gridlock appears very soon into the simulation, sometimes not at all. This is why I need to implement an additional priority system for intersections, or improve car pathfinding to escape the gridlock.

Step 4: Rewriting traffic signals

The last major rewrite was of the traffic signals system. This was probably the easiest one. At this point I was quite comfortable with how the traffic system worked. I used elm-units and elm-geometry heavily to write new implementations for traffic lights and yield signs.

Traffic lights now have a longer cycle to give cars more time to make their way through an intersection. They are used by default in all four-way intersections. A node in the road network may have a reference to a traffic light. If that node is the target of a car, the car checks where in the cycle the traffic light is. If the light is red or yellow, the car will start to decelerate in order to stop just before the traffic light (acceleration to zero at x distance). Another car may have already done the same, and in this case the collision detection system kicks in instead. Once the light is green, the deceleration or the collision avoidance is cancelled. The car goes on.

Yield signs are used by default in all three-way intersections on the orphan roads. Cars always slow down when they encounter the sign (it's also referred to by a node). If there are any other cars in the field of view of the car in question, the simulation checks if they are moving on the priority road in a way that yielding is required. The car will decelerate further on a positive match until it stops completely. Once all cars have cleared the field of view, the car will resume default acceleration. Here the dynamic field of view is essential. As the car slows down, the FOV becomes wider, until it covers all of the intersection and quite a bit of the priority road.

With the traffic signal system in place, here's Liikennematto in its current state:

Other changes and final words

Almost nothing of Liikennematto circa 8 months ago is left. The lots system covered in the last devlog is the least affected part. I have revised the core data types to work with elm-units and elm-geometry. Though the graphics seem almost identical to before, the rendering logic is new. elm-collage, which was used in rendering the simulation, is gone in favor of plain SVG. The collage features aren't required now that I have precise position information for all entities. I'm also using lazy rendering and keyed SVG objects that are not available in the library. I updated the UI with a debug side panel and compact toolbar. Everything works better with small screens, though there's work left to do.

While completing the steps above I added new debug tools. You can spawn extra cars from the toolbar. You can view new debug layers that show the road network and visualize the collision detection components of a car. Lastly, a "DOT string" of the road network graph can be exported. It shows the relationships between nodes.

I feel good about how real-time Liikennematto turned out to be. I learned a lot from working with new concepts and libraries. Realistic traffic simulation is hard to get right, and building a perfect one is not what I'm after. The result is a compromise. Some things didn't make it in yet, like the stop signs and one-way streets. They shouldn't be tough to re-implement, but I had to stop somewhere. I wanted to take a little break from Liikennematto and write this post before my summer vacation starts.

When I eventually resume, I'll take another look at the missing features and maybe work on new features, too. I'm definitely going to play with pathfinding and steering behaviors. I'm working my way through the "AI for Games, Third Edition" book, which has lots of concepts that can be used in Liikennematto.

Thanks for reading.

As always, you can play with Liikennematto right in the browser

Find what I'm up to on Mastodon!