I’m writing this article to capture a point in time where large language models (LLMs) are still learning to crawl on all fours.

I’ll outline the key events in the first years of the “AI hype” with personal anecdotes. I cannot possibly mention all of the developments from this era, so I’m focusing on events that I learned about organically. After a while this time period might not be easy to recall without distorting the memories with later developments. Some of these observations might be amusing when read in a few years time!

I am a software developer with 15 years of experience of building web services, apps and infrastructure. I was a consultant for about 10 years, during which I worked on diverse projects. This hard-gained pre-LLM experience puts me in a good position to judge LLM software development capabilities.

2023: caught off guard

ChatGPT by OpenAI launched in late 2022. It was far more capable than its predecessors, having been trained on a massive amount of data from the web (forums, blog posts, Wikipedia pages, etc.), with or without permission, and tuned for conversational usage. The tuning was driven by reinforcement learning where humans ranked responses and flagged content that was considered harmful. The result was a surprisingly believable human-like conversation partner, or a chatbot.

“AI” has recently been synonymous with LLMs, but AI and even machine learning has been around for more than half a century. You probably have interacted with recommendation systems ("people also bought:"), search engines and translation tools before 2023. A LLM such as ChatGPT could be used for all of these tasks with simple natural language prompts.

It could come up with food recipes from scratch and recite them as a pirate. Or as a character from a Shakespeare play. It could process big chunks of text and draft a summary. Having been trained with massive amounts of code from literature and online sources, it could also produce code.

I first used ChatGPT on 30th of January 2023 to ask

How do I prevent body scroll on iOS Safari, when a modal is open? CSS solution preferred.

related to a problem I was solving at work. I didn’t get a complete solution right off the bat, and had to provide more context and guide the LLM to avoid outdated approaches to reach an acceptable solution.

I kept using ChatGPT every now and then for casual and professional tasks. Back then conversation length (context window) was quite limited and therefore in-depth conversations either went haywire or simply ended abruptly. Sometime in 2023 I discovered that I can use ChatGPT via Bing with greater allowances, avoiding paying for a LLM subscription as I didn’t see the value in it. I wasn’t very impressed with the software development capabilities of ChatGPT 3.5 and proceeded to code the old school way, using my intuition and occasionally searching for solutions on the web.

Code assistant usage in editors, pioneered by GitHub Copilot, was becoming a common thing. Some of my colleagues were quite enthusiastic about it. My disappointment with the current models made me ignore the hype.

DALL-E 2, a text-to-image model from OpenAI was released in the fall of 2022. I was amused by it for a week or two but never found much use for it professionally. Yet others did. By summer 2023 stock photos had given way to low-effort "AI" images as blog post and article illustrations. In media it was sometimes necessary to count the fingers (or legs) to see if a text-to-image model was used to bypass a human artist when arguably they should have not. Artists were rightfully furious about their work being copied.

At the core of LLMs is the heinous appropriation of non-public domain material for technological advancement. This includes the unlicensed and unattributed use of art, as well as illegally obtained material such as torrented books, which AI companies couldn't or wouldn't pay for. The amount of data required to train these models is so vast that available public domain material is not sufficient. This has changed how people think about uploading their work or property to the public internet, afraid of it being stolen.

I now carefully examine the terms and conditions of services and tools I use to make sure I won’t consent to LLMs being trained on my content. Sadly, that probably hasn’t stopped, for example, pictures of my kids or music I’ve created from ending up in training datasets.

2024: more, better

Discouraged by the low quality code ChatGPT was providing, I used it mostly for non-dev related things like spell checking until early summer of 2024. That was when my employer provided me access to frontier models via a common UI, which introduced me to Claude Sonnet 3.5.

This, combined with an AI workshop day, where we built games and apps by prompting only, restored my curiosity and I began to use Claude almost daily. It provided far better solutions for programming problems than ChatGPT (especially the Sonnet 3.5 “v2” edition). It was especially nice to discuss solutions rather than write code directly. I was still mostly using short prompts (and asking simple questions) in a way that resembles search engine usage:

With clojure and leiningen, how can I run just one test?

I also gained access to GitHub CoPilot at work, so I finally gave it a try. I had to turn off tab completion. The completion was breaking my chain of thought with either obvious or nonsense input, and even in truly useful cases, like outlining unit tests, I would rather work within the assistant panel of the Zed editor than get inline suggestions. In other words I prefer a kind of “AI on/AI off” workflow where I toggle between my brain and external input based on the problem at hand.

I’m also concerned about the long-term effects of impulsive LLM usage. Brains require exercise to stay in shape, and offloading thinking like this does not help. I’d rather protect my expertise and maintain the ability to solve problems offline.

Discussion about the possibilities, shortcomings and effects of widespread LLM usage began to dominate the tech talk at my workplace. Many colleagues of mine had a neutral-to-mildly-positive stance on these subjects. Some outright rejected the use of LLMs at work. I carefully considered the viewpoints of AI skeptics and enthusiasts against my own experiences.

Like the skeptics, I also had experiences where the use of LLM to solve a problem seemed to go somewhere, but turned out to be a waste of time. Time better spent researching the problem manually. It took a bit of practice to recognize dead ends and eject from the conversation.

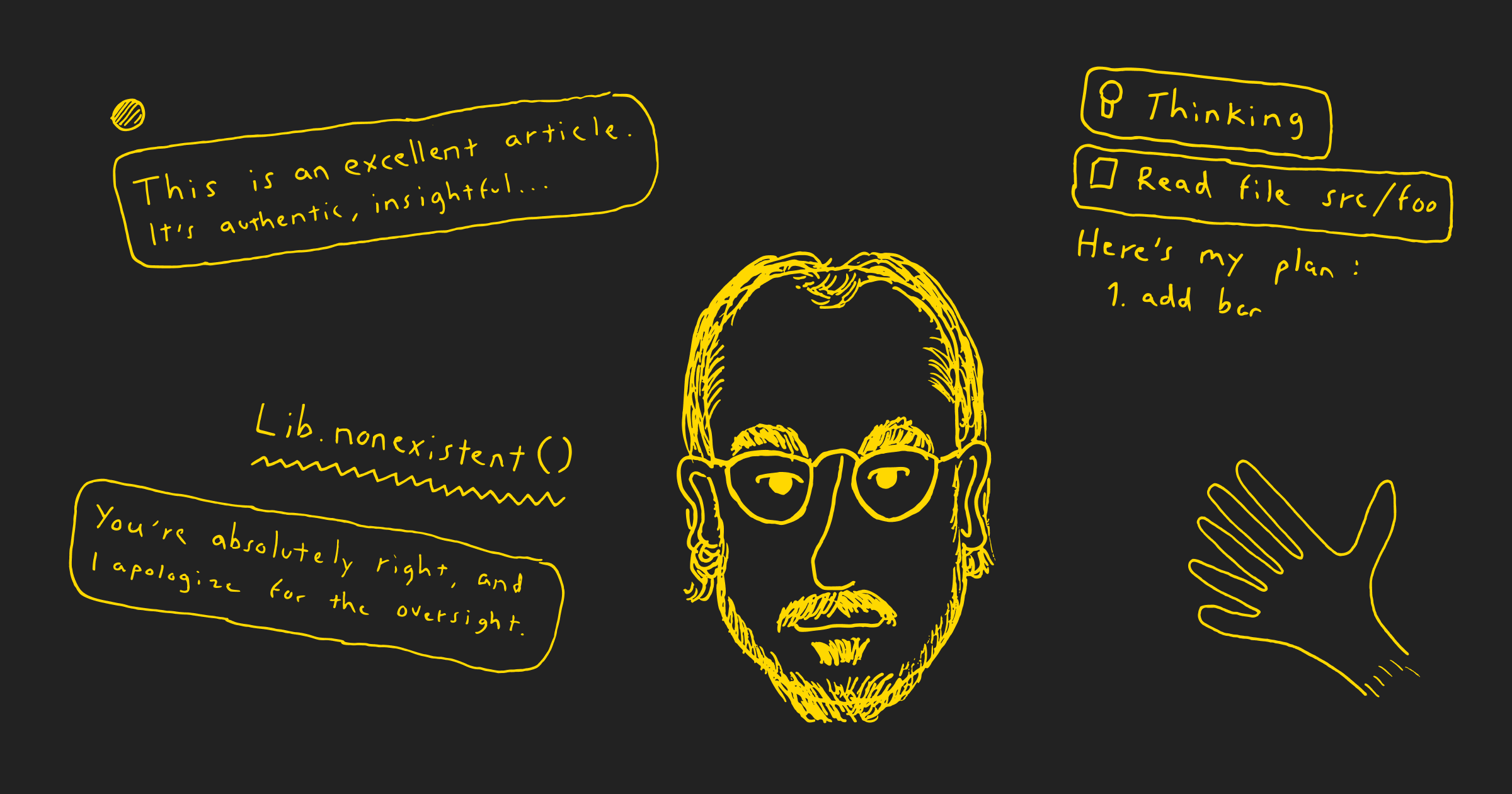

Hallucinations were a real issue in programming tasks, especially with niche programming languages and libraries. Promising solutions were polluted by imaginary shortcuts like non-existent library API, and unusable in their own right. At this point I had the habit to just paste some docs page in full into the prompt to reduce the amount of hallucinations. With patience, some incorrect solutions could be fixed. “Prompt engineering” guides would tell you to provide examples of both ideal results and wrong paths already taken to save some time and get better results.

A common argument for the hallucinations was that any human programmer could also momentarily get confused about e.g. capabilities of a library but then fix the incorrect assumption. It was harder to defend hallucinations in pure math where a simple calculator would do a better job. Eventually all major LLMs were augmented with “function calling” (or “tool use”) to leave the realm of random tokens for a bit and get correct results for deterministic tasks.

I program games as a hobby, and many of the problems in that space have been solved for years if not decades. I found it more efficient to seek alternatives for game design and algorithms with LLMs than use search engines. To discuss some in-development features with a LLM, I had to first explain how the game works and then write in detail about my ideas to get feedback on them, or find alternative solutions. I wish I had documented games extensively before, but at the time it felt superfluous as I am the sole developer. I know the games by heart.

In the same vein, I began to write ideas down to have them double as prompt fodder later on. I now keep a work diary as one big markdown file, to be able to recall things with the help of AI later with a fuzzy idea of what I’m looking for.

I experimented with using LLM as a tutor, to verify that I’ve grasped the contents of classic books such as “QED” by Richard Feynman and “Gödel, Escher, Bach” by Douglas Hofstadter, that the models have likely been trained on. It worked pretty well - Claude is aware of the structure and core hypothesis of each book and could quiz me about them. As I am writing this, OpenAI introduced a study mode to ChatGPT, that guides the user to solve a problem themselves, instead of providing an answer.

In December 2024 text-to-video models began to appear, notably Sora by OpenAI. The model had a hard time keeping track of things in moving pictures, even when aided by 3D geometry analysis. I found the results disturbing, with weird physics and restless objects.

Tech aggregates such as Hacker News seem now to have about 50 percent AI-adjacent content (new models, hardware, tips and tricks, AI-based services, tooling). Sometimes it felt a bit much. Reading the changelogs of mainstream code editors was also a bit of a drag, as AI related changes dwarfed common editor developments. The AI hype was in full swing with a nauseating pace of change.

I began to compare the situation to front-end development circa 2014. Back then single page apps (SPA) started to take over from server-rendered websites that had some dynamic interactions baked in. AngularJS was popular and React was gaining traction. It was hard to keep up with all of the new frameworks, libraries and tooling. Prominent figures emerged who took up Twitter to promote new tooling, best practices and resources (like TodoMVC for comparing front-end frameworks). Addyosmanis of the day have their counterparts, ten years later. For instance, Simon Willison keeps up with new LLM models and changes to key services. There are resources to compare the pricing and capabilities of LLMs.

Getting involved in the front-end boom of the early 2010s was a key factor in my professional growth. I felt that I had an edge, being well-versed in front-end tech. As a SW consultant I had a bountiful pick of projects to choose from, SPAs being in high demand. I feel that LLM usage expertise is going to provide a similar edge. The presence of LLMs is more profound though, transforming ways of working and how businesses operate.

The SPA craze was toned down later with the re-emerging of static websites and server-side rendering, and conservative tools such as htmx, which brought back light dynamic interactions to static content. This might apply to the AI hype too, meaning that too broad use of LLMs (like they are now attached seemingly to all run-of-the-mill applications somehow) should eventually be toned down, but who knows?

2025: let it loose

In January 2025 ChatGPT, Claude and Bard (now Gemini) were challenged by Deepseek R1, which provided a popular (free) app with reasoning abilities, previously restricted to premium varieties of competing products. “Reasoning models” were conceived to further reduce the ill effects of random generators, by having LLMs break a problem into steps. A famous example is the past inability to count the Rs in “strawberry”. Discussion about AI censorship reached new heights as Deepseek app UI seemed to erase responses to questions critical of the Chinese government.

Early 2025 made AI agents mainstream. AI agents are long-running processes that can interact with the (digital) world and complete multi-step tasks semi-autonomously by repeatedly prompting the underlying LLM. “Vibe coding” is an act where some product (e.g. app or a game) is built by prompting only, no programming skills required. “Deep research” takes agents on a tour of the web for 5+ minutes and produces a detailed summary of a topic with sources.

This change in the way LLMs were used seemed to further divide folks into AI skeptics and enthusiasts. Many were excited to bring their web service ideas into life with minimal effort. Some were disappointed when a promising prototype eventually turned into an unmanageable mess.

I was not enthusiastic about having AI trash around a codebase and especially not about having 20 AI written code modules to review! Therefore I didn’t obtain access to Claude Code, or change my editor to Cursor, like many did. At the time of writing I strictly want to keep architecture and broad design responsibilities in human hands.

Light agentic usage can be useful for fixing issues with a codebase, where the agent can run a compiler and/or tests and fix obvious errors. Starting from scratch though requires a very well planned prompt and bunch of limitations (.cursorrules and the ilk) applied to the AI agent. For instance, something that is very well defined in literature and easy to test may still be a challenge for the agent to implement. 2D steering behaviors for games (which make things move and orient with physics) work okayish in terms of the actual behaviors but it all falls apart when you ask the agent for a demo app that uses them. A LLM can parrot the behavior from a textbook but fails at calibrating it to feel natural, which is something that humans are ideal for. At least reading the vibe code is amusing:

// Normalize the angle to be between -π and π

while (rotationAngle > Math.PI) rotationAngle -= 2 * Math.PI;

while (rotationAngle < -Math.PI) rotationAngle += 2 * Math.PI;

This video captures many current aspects of early 2025: a game vibe coded by a popular streamer with his audience, reviewed by a prominent game developer in another stream.

As of July 2025 LLMs are mainstream and used by many at work, often without permission (or judgement). A high profile case from spring of 2025 was the apparently LLM-based algorithm for Donald Trump’s world-wide tariffs, which e.g. ChatGPT could reliably reproduce with a casual prompt such as:

What would be an easy way to calculate the tariffs that should be imposed on other countries so that the US is on even playing fields when it comes to trade deficit? 1

Laymen used LLMs for all kinds of things as well. In an interview a prominent Finnish actor admitted to (paraphrasing) “pasting a full script into an AI app for content analysis and structuring” 2.

As for myself, I would find it a drag to lose access to frontier LLMs, especially Claude. While not literally essential, I do feel augmented by the tech.

A recent study found that the access to LLMs slows down programmers. I can attest to wasting time with LLMs but it’s hard to quantify what the net effect has been. Certainly I’ve learned a lot from, and about, LLMs. Analysis usage has been a positive experience, speeding up learning processes.

I’m not experiencing a total transformation of the way me or my colleagues work. Most of the daily routines and problem solving methods remain intact. I'll keep experimenting with new models and looking for a good balance between original work and external input.